- I mentioned in a previous post that I had a lot of apprehension about going on a trip to S.E. Asia to learn about sex trafficking. When I saw our schedule, one thing stood out to me: we were scheduled to hire a prostitute and pay her for an interview so that we could hear her story. This seemed daunting to me. I mean, it was one thing to see these girls lined up like an auction block at the “go-go bars” (brothels), but sitting face-to-face felt so raw and so personal and so vulnerable. I was also really worried because I didn’t want the situation to feel exploitive. I didn’t want the girls we talked to to feel like we were judging them or mothering them or viewing them through a lens of cultural superiority. So when this night came around, I was nervous.

- have they been taken to another country where they don’t know the language and are isolated?

- do they have few resources to leave?

- have they had their passport taken away?

- are they free to leave or are they being held?

- has someone created a debt that they must work off?

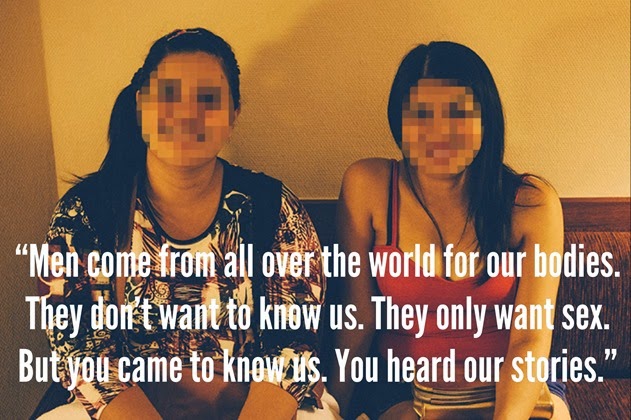

Around 9pm, we set out to hire two girls. We decided to interview two at once because it might put them more at ease. Laura Parker, the wife of the Exodus Road’s director, took a translator and walked along the beach-front street that is lined with freelance prostitutes and talked with several girls before deciding on two that stood out to her. The girls understood that we were writers and wanted to share their story, and they agreed on a price that was very generous for their time. We agreed to obscure their faces and use pseudonyms. I’ll call them Sai and Nam.

We interview Sai and Nam in our hotel room . . . the four bloggers and Laura seated on the ground or on the bed, with the girls and a translator on the sofa. We had pre-arranged a list of questions that were intended to be respectful but also to get to the realities of their lives. Well, we didn’t even make it through the first question. The girls were so eager to talk. My fears about respect and exploitation were completely wrong . . . they wanted to be heard. They talked so much that at the hour point, which is the time we agreed to pay, we had to stop them and offer to pay them for another hour. They readily agreed . . . I think they would have kept talking even without the extra money. They had stories they wanted to get out.

Nam shared her story first. Nam was a cute girl who appeared in her late 20’s. She came in wearing a very short skirt and grabbed a towel from the bathroom to place over her legs. Despite seeming a bit embarrassed at first, she quickly spilled her story. She grew up in a household with a verbally abusive mother. Her father abandoned them. She said she never felt loved. She turned to drinking and partying in her teen years. At one point, her mother told her that since she was sexually active, she might as well make some money doing it.

So Nam called her mom’s bluff. She got in touch with a pimp who smuggled her into Bahrain to work in the sex trade. Nam said that her intention was to call her mom and tell her that she’d moved to Bahrain to be a prostitute to prove a point (and get a little revenge.) A typical teenage move . . . a dramatic phone call home which would hopefully get her mom’s attention, but Nam had no intention of staying. She realized upon arriving that she was not allowed to leave. Her pimp took her passport and informed her that she was now in debt for the costs of her travel. She worked for two years to pay that debt off. At that point she was finally able to make money on her own, and Nam stayed on because she didn’t know what else to do with her life. During this time, she became addicted to crystal meth and met a boyfriend she describes as abusive. She became pregnant but had an abortion. She was still a teenager. She was tearful as she recounted the way her treated her, but he was a ticket out of Bahrain and back to her home country. Eventually, she made her way to the town where she currently lives, because she had heard prostitutes could make a lot of money. The town’s number one economy is catering to foreign men seeking sex.

Nam has since had another child, a 9-month-old who lives with her boyfriend, who doesn’t work. She is frustrated that her boyfriend doesn’t have a job, but her earning potential as a prostitute is much great than his so he pressures her to continue. She feels trapped, both in her job and in her relationship.

Sai appeared a bit more shy than Nam, but as her friend shared she became bolder. It was clear these two were a huge source of support for one another. Sai’s story was quite similar to Nam’s. In her late teens, Sai was recruited to go work in Singapore. She was taken there and then her passport was taken away. Like Nam, she found herself in a situation of bondage . . . she was forced to pay off a debt to her pimp for several years.

The similar stories these girls told made it abundantly clear that while sex work may be a choice for many women, it’s also true that many women were initially trafficked into prostitution. Just the previous day, we’d sat in the offices of the Exodus Road as they explained the difference forms of trafficking, and the questions they ask to ascertain whether or not a person is a victim of trafficking:

We asked two random women from the red light district to tell us their stories, and unknowingly found ourselves face-to-face with the heartbreaking reality of sex trafficking. These women had experienced it first-hand. And yet, they didn’t even see themselves as victims. This was normal to them . . . a part of life that was familiar to many of their peers. Something so unthinkable to us is commonplace with them.

Sai revealed that she had three children she supports who live elsewhere. Two live with their father’s mother and one lives with her own mom. She also told us of her boyfriend from Singapore. He’s married and has children back in Singapore, and acts as her pimp here. She’s supporting all of them. As she tells the story, you can hear the frustration and anger in her voice. “I’m so stupid,” she says. “Because I love him and I know I should leave him but I don’t. He takes advantage of me but I love him.” We all assure her that we get it . . . that we’ve stayed in bad relationships. There are tears and laughter as we relate to this human experience but also a recognition that her reality goes beyond what any of us can understand.

She tells us how lucky we are to be able to live with our children. She doesn’t have lofty dreams or occupational goals . . . her one wish is to be able to live and work in a way that allows her daily interactions with her kids. Something most of us take for granted.

Sai then reveals that she is pregnant. She tells s that she is 4 months along and hoping she can work until month 7. We ask her how that works with clients and she explains that she can usually hide it at first, but that many clients get angry when they discover it. “They see my belly and then the want to pay me less.” She has worked through all of her pregnancies. After each child, she started working again within a few months.

At this point, Sai, who was initially the shyer of the two, turns to her friend and whispers emphatically. It’s clear that she is urging Nam to tell us something. And after some deliberation Nam tells us that she, too, is pregnant. She is visibly upset to share this.

We tell them that we think they are brave. We tell them that we are proud of how committed they are to supporting their kids. We tell them that we would do the same thing, and we mean it. We tell them that we think it is unfair.

They nod in agreement.

“You are the lucky ones” Sai says, motioning to us through tears. “You have an education. You get to go to work and be with your kids. That is all we want. But we cannot raise our kids doing the other jobs. We won’t make enough money. We can’t leave this work.”

In that room, I think we all felt an overwhelming sense of empathy and connection. I fought the urge to try to fix things, and instead to just sit with them and empathize and listen. We reiterated that we felt it was not fair that such disparities exist based on where we were born. They seemed relieved to hear us acknowledge that. I think we all sat in that room feeling that we are so much alike. I couldn’t help thinking that it is women who really need to rise up and help one another. These girls are our sisters, born into different circumstances, and doing what they need to do to survive.

As they left, Sai and Nam told us how much the interview meant to them. “This money means something because we made it with our stories and not our bodies. And because we made this money from women.”

And then . . .

“Men come from all over the world for our bodies. They don’t want to know us. They only want sex.

But you came to know us. You heard our stories.”

Our time with Nam and Sai was incredibly emotional, and there is no way I convey the sense of female connection in the room that night. It was also a heartbreaking smack in the face with my own privilege . . . privileges that I hadn’t even been aware of. The privilege to get an education, of course . . . I knew that. But the simple privilege of raising my own kids, of owning my own body, of not needing to sell myself to survive.

We are swimming in privilege, but I refuse to swim in guilt. This encounter only strengthened my

resolve to use my privilege, and I’m proud to share their stories here, because they want us to hear them. Their stories are important. And their stories, particularly of being placed into indentured servitude, represent so many other women in S.E. Asia. They represent why the work that Exodus Road does is so important.

So thanks for listening, and thanks for sharing.

I still have a few more stories to share in the next week. I want to do diligence to each one. And then I’ll be offering some ideas of how you can get involved with the work the Exodus Road is doing.