As we celebrate the impact of Dr. King today, I’ve seen many links to posts about how to talk to kids about Dr. King. I’ve seen resources to books and movies that help children understand racism and the importance of avoiding prejudice. I’ve written one myself. But as I’m reflecting on how we really show our kids these values . . . and how we, as adults, live out this dream that Dr. King gave his life to fulfill, I am reminded that books and movies are not the full picture.

I was thinking on my own childhood, trying to recall if there were books and movies that impacted my own view of racial reconciliation. In truth, I cannot remember a single story or film. I can’t even remember a conversation about race. So how, then, did my parents so clearly communicate these values to me? They lived it.

As a young child, there were two men that I remember clearly as close friends of our family. Bill was one of them. He was a tall, middle-aged black man with eyes that crinkled when he smiled. My parents were very involved in Tae Kwon Do, as was he, and the developed a close friendship. Bill was a gentle and funny man. He and his wife got married at our house . . . probably the first time I was in the minority in a situation as a child, but definitely not the last.

The other man was Minucher, a jovial Iranian-American who was also involved in karate. He developed a friendship with my parents in the mid-80’s, at a time of great hostility towards Iranians. He was a burly man with coffee-colored skin and a thick moustache. I remember many road-trips with Minucher as we traveled to karate tournaments around the mid-west. He had a daughter our age, and he loved to make us laugh. When we got bored and cranky in the car, he would point to imaginary rabbits and deer outside the car window. We knew he was pretending but we still played along.

My parents never talked to me about “tolerance” or acceptance in relation to Bill and Minucher. They could have, but they didn’t need to. They were living it. These men were a part of our lives in real and significant ways. And later in life, when the media and society-at-large told me that black men were to be feared, or that Middle-Eastern men warranted suspicion, I didn’t have to recall a book or a DVD or a platitude I’d been told. I had grown up in relationships with real, in-the-flesh people who dispelled these stereotypes in a way that no story ever could.

It’s easy to give our kids lessons from a book, but if we really want to honor Dr. King’s dream, then diversity should be reflected in our lives. It should be reflected in our friendship circle, in our church community, and in the people we welcome into our home. Otherwise, when we talk with our children, diversity is simply a “do as I say, not as I do” concept. If we teach our children to value people of all races but don’t live a life that reflects that value, then our underlying message is that racial diversity is a merely lip service . . . something that sounds nice to say, but that we don’t really mean.

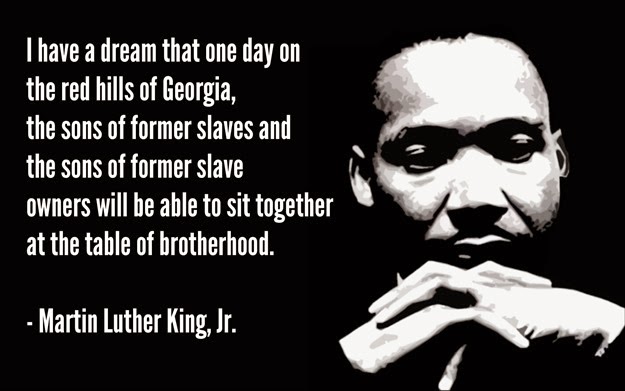

Martin Luther King Jr. paved the way for possibility . . . but if we don’t take hold of that possibility and truly be in fellowship at the “table of brotherhood” with people outside our own race, then his dream is not yet realized.