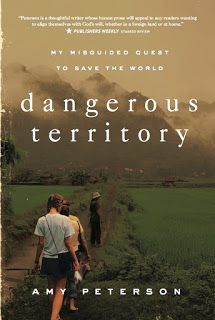

The following is a guest post by Amy Peterson

My book Dangerous Territory: My Misguided Quest to Save the World released this month. The magazine Christianity Today asked to publish a lightly-edited excerpt from the book, and I agreed to let them; but at the last moment – literally – they pulled the piece, citing concern that publishing it might cause their readers to doubt their commitment to the cause of cross-cultural evangelism. They were afraid of entering into this conversation.

But I believe we are ready for this level of nuance, and we shouldn’t be threatened by tough questions.

Read the excerpt, and judge for yourselves.

When, at the age of 22, I moved to Southeast Asia to teach English in a university, I had reservations about using the word missionary to describe myself. For one thing, I was aware of the ways that, historically, some missionaries had been complicit in violent, imperialist endeavors. I was afraid of taking on a moniker linked to that heritage. Also, I was headed to a closed country—one that forbid evangelism and didn’t allow missionaries to enter. I wasn’t entering under false pretenses. The government and university administration knew I was a Christian English teacher, so that was what I preferred to call myself: a Christian English teacher.

At the same time, though, I was headed to Southeast Asia at least in part because I was looking for the kind of spiritual adventure that I’d read about in missionary biographies. I wanted an extraordinary life, flush with spiritual vitality, fully committed to God. I wanted to be the greatest Christian, and I believed missions was the key.

I still can’t tell you where I was teaching that year because my students and friends remain in danger there. As I’ve processed what we experienced together more than a decade ago—the miracles, the tragedies, the sense of God’s absence and of God’s presence, too—I’ve grown even more wary of that word: missionary. It may be time to retire it.

Historical Baggage

Missionary was first used in the English language in 1625 by Edward Chaloner, a clergyman in the Church of England. He was a preacher, a writer, and an academic. In his work, you find nuanced arguments and a careful attention to words. One of the big questions of his day, for example, was whether the Church of England had been born from the Roman Catholic church, or had originated separately. Chaloner said that it wasn’t an either/or question: The Church of England in its earliest days consisted of reformers who had broken all ties with the Catholic church as well as all who kept in their hearts the simple faith of the early church, whatever denomination they found themselves in. Chaloner valued all truth, staying up to date on scientific developments, quoting ancient philosophers and poets, and studying Roman Catholic theology.

It’s no surprise that a guy who loved language and the church so much would be the one to introduce the English term missionary, borrowed probably from French (missionnaire) or Spanish (misionero). He died of the plague at age 34, the same year he wrote about Jesuit missionaries.

I have to wonder what Chaloner, with his love of precision and care for words, would think of the way this word has evolved in the 400 years since his death.

In the beginning, missionary had a limited meaning: a celibate male, probably in a Catholic order, probably European, who had made a life commitment to evangelism. But almost immediately that definition was complicated by the association of Catholic missionary orders with political colonization. The expansion of God’s kingdom was in many ways conflated with the expansion of territory controlled by Catholic kings, and their quest to acquire land, labor, and raw materials.

The Protestant missionary movement did little to improve the associations. While Catholic missions had been inextricably bound to political expansion, American Protestant missions were born entwined with corporate-style capitalism. The first missionary boards were structured after secular trading societies, and their values were efficiency, production, and numbers-based assessments.

The word missionary, then, was born into the English language already weighted down with imperialist and capitalist baggage. It evolved and lost some of the negatives, though it would never shake them entirely, which is part of the reason people still give you the side-eye if you say you’re a missionary.

A Calling for Spiritual Superheroes

The definition changed in some important ways, though, over the next couple of centuries: now the (imperialist, capitalist) missionary was not necessarily a celibate male committed for life; the missionary could be married, could be non-western, could be a woman!

And then, somewhere around the late 1800s or early 1900s, the word acquired a new set of connotations. Now missionaries were God’s Special Forces. They were adventure heroes and “grabbers of the impossible,” those who gave up “small ambitions” and went where the “real action” was. And this posed a new set of very current problems for the word.

The missionary vocation was marketed to a generation of us as the most spiritual vocation. We read biographies that were “high adventure as unreal as any successful novel,” in the words of missionary Nate Saint. Amy Carmichael told us that “God’s true missionary is a Nazarite, who has ‘made a special vow, the vow of one separated, to separate himself unto the Lord.’” We began to believe that there were “holy” jobs and “ordinary” jobs, that some callings were simply more spiritual. And the music on the video or the conference stage crescendoed while a voice asked us to go, and we felt in our hearts that to go was always more noble than to stay.

The missionary vocation was marketed to a generation of us as the most spiritual vocation. We read biographies that were “high adventure as unreal as any successful novel,” in the words of missionary Nate Saint. Amy Carmichael told us that “God’s true missionary is a Nazarite, who has ‘made a special vow, the vow of one separated, to separate himself unto the Lord.’” We began to believe that there were “holy” jobs and “ordinary” jobs, that some callings were simply more spiritual. And the music on the video or the conference stage crescendoed while a voice asked us to go, and we felt in our hearts that to go was always more noble than to stay.

The problem is that we went, and it wasn’t all high adventure. Or we went, and we developed overinflated senses of our own spiritual importance. Or we went, but we were unprepared for the realities of cross-cultural work, ill-equipped to serve in meaningful ways.

Or the problem is that we didn’t go, but we believed the fact that we stayed made us second-class Christians. We stayed, so we thought that we were not called to evangelism like the missionaries were.

No vocation is more spiritual than another. And every Christian is called to share the gospel. But the very existence of the word missionary as it is used today seems to imply otherwise. If missionaries are God’s Special Forces, then evangelism is a calling for some, for the super-spiritual. The rest of us just aren’t called to that.

Our Shared Vocation

Perhaps the word missionary has become more problematic than helpful. Instead of describing reality, it blurs our vision and limits our imaginations. It has outlived its usefulness, and I vote we give it a proper burial.

We need new ways of talking about God’s work in the world. It’s true that God is “on mission” to reveal his glory and love to all nations by spreading his kingdom on earth, and that we are to join in that mission, all of us. But God’s mission has never been about counting the number of spiritual conversations you’ve had in a week or valuing street evangelism over changing diapers and formatting spreadsheets. God’s mission has never been about seeing yourself as a spiritual superhero in an action story. God’s mission, as St. John of the Cross said, is to put love where love is not. It’s about relational flourishing.

We all share this vocation, but we live into it in different ways. Maybe your way is through cross-cultural evangelism. Maybe it’s to be a first-grade teacher. Maybe it’s to be a linguist and a Bible translator. Maybe it’s to be a stay-at-home dad. Maybe it’s to be a doctor in the suburbs, the inner city, or an African village. I don’t know, but what I do know is that all of those vocations are valuable, and in all of those vocations, you can put love where love is not.

_________________________________________________________

Amy Peterson is the author of Dangerous Territory: My Misguided Quest to Save the World . She lives in rural Indiana with her husband and two children. Find her on Twitter at @AmyLPeterson.

I have to agree that being labeled a "missionary" can be a challenge. I'm not special or more holy than anyone else. I answered God's call like millions of other Christians…mine just involved moving to the other side of the world. My work isn't always glamorous or extraordinarily spiritual. I can shop at the mall, go swimming in the pool (conveniently located at our team house), and eat McDonalds and KFC. I don't want to be put on a spiritual pedestal. I want people to see that being a missionary is being obedient to God's calling and doing what He tells you do, no matter when and no matter where.

Thanks for posting this.